What is the true face of Anne Boleyn? New Evidence & Facial Reconstructions

What is the true face of Anne Boleyn? There is some new compelling evidence that has come to light in the last few years about a lost portrait - called the Lumley Portrait - that may reveal Anne’s true, painted-from-life face to us. I want to talk through this new evidence today and of course bring you some new facial re-creations, since Anne is one of my favorite subjects to talk about.

Full video with history and additional re-creations available on YouTube:

Anne Boleyn is notorious for being the second wife and Queen of King Henry VIII of England - eventually being wrongfully executed on his orders in 1536.

The Moost Happi Medal - the only contemporary image known to exist of Queen Anne Boleyn.

The reason it’s so hard to get a picture of the true Anne Boleyn is that after her death, her image was essentially erased from England. Anything that bore Anne’s symbol was struck down (making artifacts like this wooden falcon , a symbol of Anne’s, exceedingly rare.)

The only portrait known to be of Anne Boleyn made during her lifetime, is called the “Moost Happi Medal”, and even despite attempts at restoration, it’s still a really poor image.

The political atmosphere in Tudor England after Anne’s death was so incredibly tense, that anything that remained of the disgraced Queen - clothing, images, or artifacts - to survive, would have to have been kept secret by her kin, and then kept safe enough to last throughout the centuries.

The possible photograph of the lost Lumley Portrait, captured in the 1920’s by the Howard Young Gallery.

One such portrait, which is unfortunately lost to us at this moment, was known to exist as late as 1773. This is known as the Lumley portrait.

Authors Elizabeth LaVasse and Richard Masefield have studied its trail, bringing us new insight.

The Lumley portrait was a full-length, contemporary image of Queen Anne Boleyn that once hung at her childhood home of Hever Castle. It was possibly commissioned by her father, Thomas Boleyn, which is one reason why may have been able to survive - her family would have protected it at all costs.

Henry’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, eventually leased Hever Castle in 1540, just four years after Anne Boleyn’s death. We don’t have a record of how Anne of Cleves felt about her predecessor, but this shows us that she had enough admiration and respect to keep this portrait safe, which I find a little heartwarming. At the end of the day, both women were victims of Henry VIII.

Anne of Cleves kept it until her death in 1557, when she willed it to her friend, Henry Fitzalan, the Earl of Arundel, who then willed it to his son-in-law, Baron Lumley - which is why we call it the Lumley portrait today.

Sometime during the reign of Charles II, in the mid-late 1600s, a fire unfortunately damaged the portrait, and it had to be cut down to a shoulders-up version.

Being over 150 years after King Henry, Anne, and the whole Church of England break from Rome debacle, these events would no longer be fresh or sensitive, they would just be history. There was no need to hide Anne Boleyn’s image any longer.

A traditional Long Gallery, with portraits of past royals.

It was common for nobles, in their lavish estates, to establish “long galleries” - basically Halls with portraits of past kings and queens hanging in them. They wouldn’t have original portraits to use of course, so they would commission artists to create copies of existing portraits of royals.

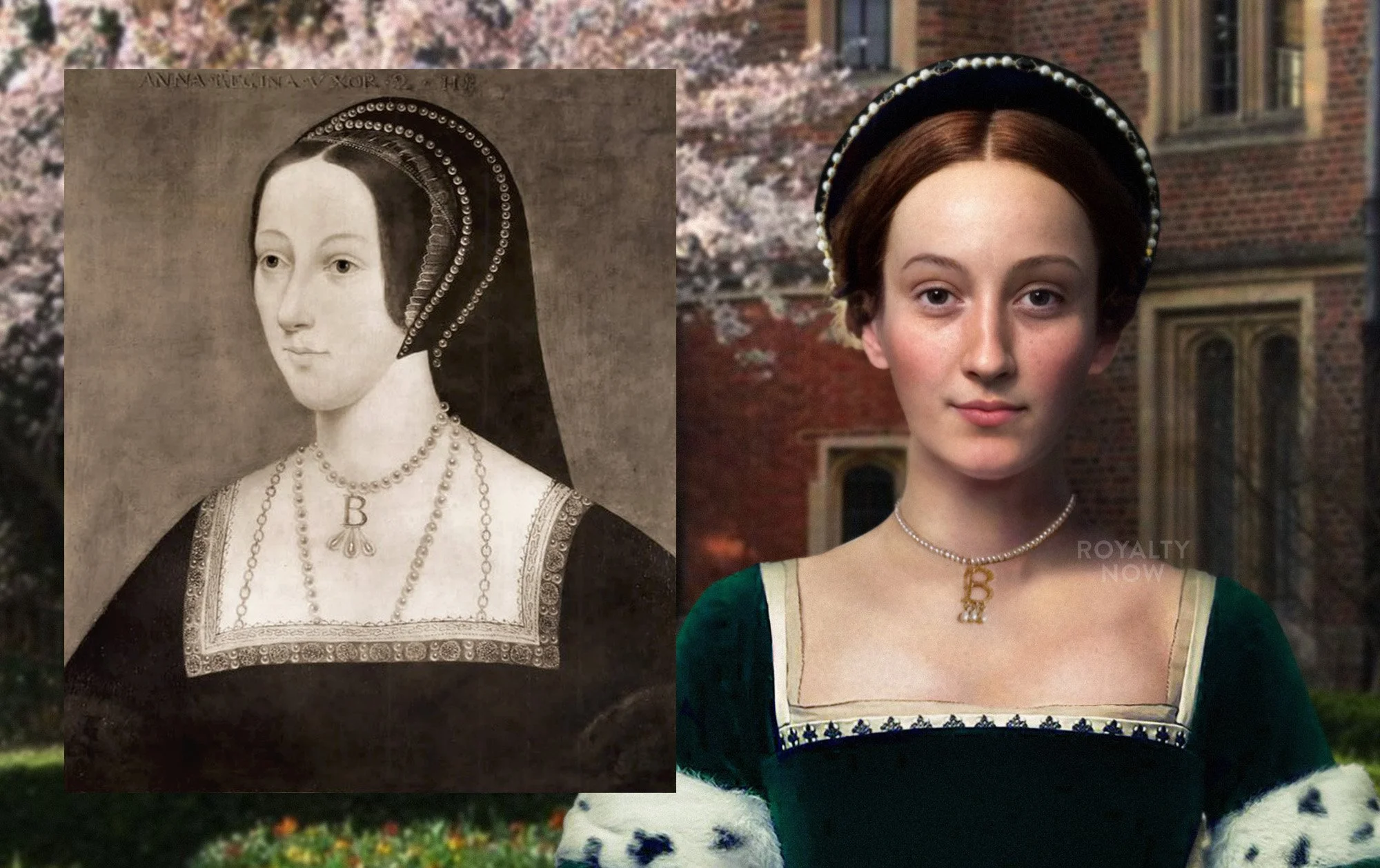

This is when we see a boom in copies of an Anne Boleyn image being created. The Lumley portrait undoubtedly showed Anne wearing the classic pearl-lined french hood, black dress, and famous B pendant. We know this because of the sheer amount of copies made with this same outfit, all cropped in the same shoulders-up frame.

Some copies, of course, are better than others.

After this, we know the painting was sold to a private collector in 1773 - and this is where it evaporates from the records, until, mysteriously, in 1926, the Howard Young Gallery photographed a portrait of Anne that no longer seems to exist.

The original photo, in sepia, is beautiful (above). Many assumed that a lost original portrait of Anne would have been painted by Hans Holbein, the ubiquitous court painter, but analysis of this image reveals that it actually has a lot more in common with the style of Joos van Cleve, who also painted Henry VIII from life in several images. Van Cleve would have been in England for this commissioned portrait of Henry in 1532, and could have made this portrait at that time as well.

The Lyndhurst Portrait.

One very interesting thing about the Lumley portrait that historian Adam Pennington points out, is the pattern of pearls beneath Anne’s B necklace. Do you notice how they are splayed out and separated? There is only one copy in existence with this exact pearl pattern, and it’s referred to as the Lyndhurst portrait.

But the pearl detail is a very interesting one, and to me it perhaps indicates that the Lydhurst was one of the earliest copies of the lost original.

But to some scholars, it indicates something else entirely. It turns out, the Lumley portrait and the Lyndhurst portrait are both painted on panel. The two happen to have identical dimensions, identical inscriptions, and identical silhouettes. Is it possible that the Lyndhurst version is one in the same with the version photographed by the Howard Young Gallery in 1926? Maybe unrecorded restoration work discovered that the Lyndhurst is actually the original, lying in wait under a layer of overpainting?

Honestly, I’m skeptical of this, just because the photographed version looks like it was painted by a much more skilled artist. This version looks to me like a clumsy copy.

Something else interesting about the 1926 photograph, and the Lyndhurst, is that Anne’s hair appears to be dark red, rather than the typical dark brown or black. This is also present in the John Hoskins Miniature, which was painted in the mid-1600s, and on the back is noted as being a direct copy of “an ancient original.”

So it would appear that some of the most direct copies of the lost original show much more vivid red hair than other, later copies. I mean, this makes sense, her daughter Elizabeth was famous for her red hair, and it was very very common in Tudor England to be blonde or red headed.

The physical descriptions of Anne from her life all mention her beautiful dark eyes, but never her exact hair color. It’s very possible that Anne Boleyn was a redhead, or had more auburn hair than later portraits would suggest.

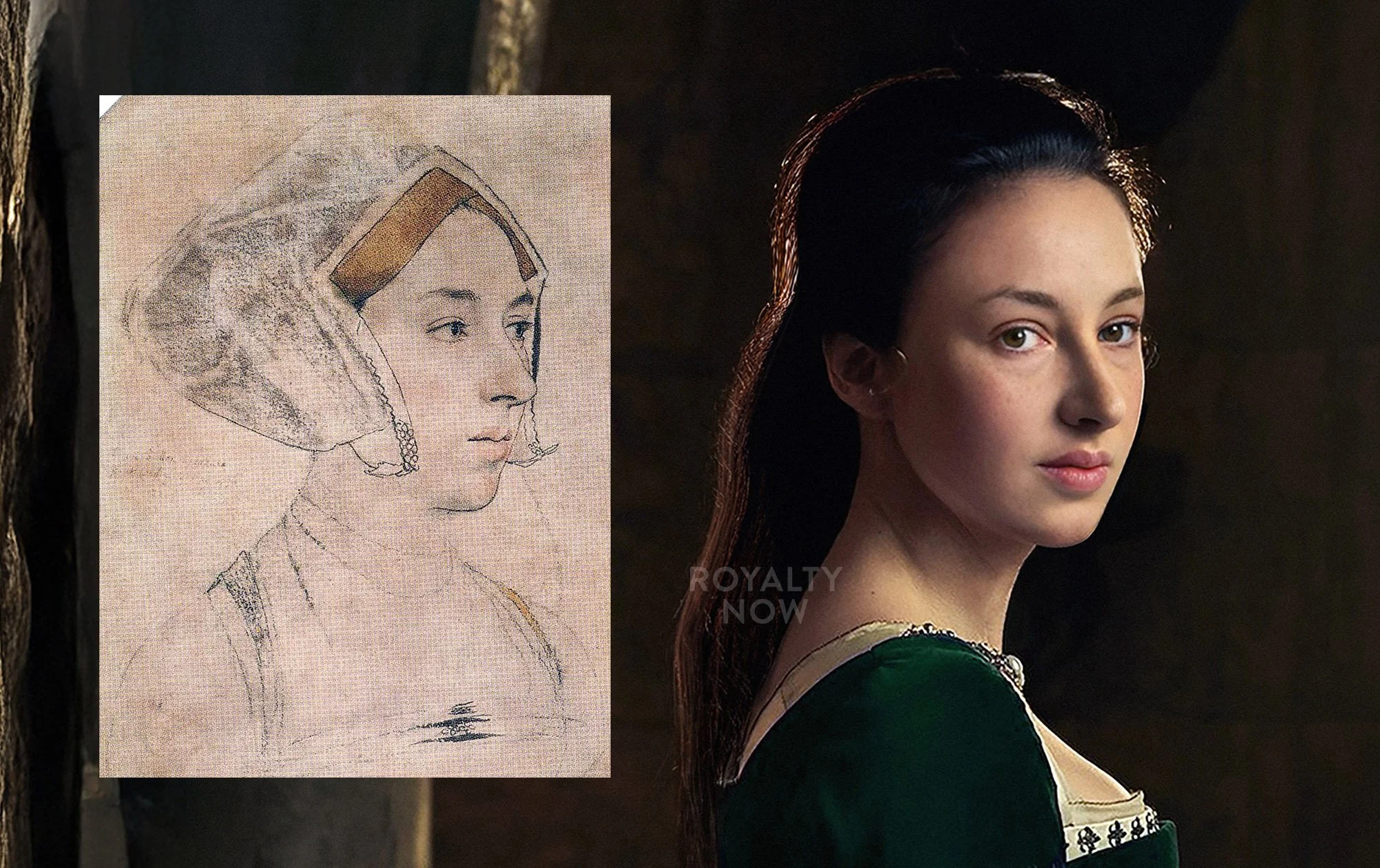

Let’s also take a look at the sketches of a woman by Hans Holbein, purported to be Anne. Don’t they resemble the Lumley portrait much more than other famous copies, like the one from the national portrait gallery?

They share the same strong, sloped nose, fuller mouth, and soft, slightly recessed chin, unlike other copies created later.

A venetian ambassador even described Anne as having a full, wide mouth, which is in direct contradiction to all of the copies with these tiny, pinched lips. But I suppose all it takes is one artist to paint tiny lips and then have all of the copies kind of play telephone with that feature.

To me, the sketches and the Lumley portrait are also the only versions consistent with the Moost Happi medal, which is the only indisputable image of Anne from her time as Queen. It’s been badly damaged, and looks a bit squished, but it does show Anne with a fuller nose and mouth than are present in other portraits.

In my re-created version, I see a lot of resemblance between this sketch of her brother, George Boleyn, and this miniature that is assumed to be of her sister, Mary. They all look like they could be siblings, which to me lends credence to all three images.

Comparison of sketch of George Boleyn, possible miniature face of Mary Boleyn, and my re-creation of Anne Boleyn from the Lumley Portrait.

So let’s take a look at the face of Anne, re-created from the Holbein Sketch, and the Lumley Portrait:

Anne brought to life from this possible Holbein sketch.

A forward-facing reconstruction of the Lumley image.

Anne Boleyn brought to life from the Lumley portrait.