What did Mary Boleyn (“The Other Boleyn Girl”) really look like?

I want to talk today about another Royal Mistress, Mary Boleyn - the overshadowed elder sister of Anne Boleyn, and a prominent member of the Tudor court. She was a mistress to two kings, who happened to be rivals, Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France.

Her life is quite mysterious, and what we know about her is full of myths and half-truths - with Phillipa Gregory’s entertaining but not so accurate story, The Other Boleyn Girl, to thank for many of them.

Historian Eric Ives has said that what we actually know about Mary Boleyn could be written on a postcard with room to spare, which is a great way of describing it, so let’s review what’s on that postcard, shall we?

Full video with history and additional re-creations available on YouTube:

What do we know about Mary Boleyn’s life?

Much like her sister Anne, Mary’s early life is a bit mysterious. She was probably born sometime around the turn of the 16th century, to Elizabeth Howard and Thomas Boleyn.

In 1514, Mary attended King Henry VIII’s sister as she set out to marry Louis XII, the heir apparent of France. Although Louis died just 3 months later, both Mary and Anne stayed in France to serve the new Queen, Claude.

Francis I of France

She would have been educated in French, and taught the same courtly wit and flirtation as her sister, Anne. Overall it was seen as a feather in the Boleyn girls’ caps that they were educated abroad - it made them very sexy and worldly to the English.

However, during her time in France, Mary seemed to have gained a reputation for being promiscuous. It was rumored that she had begun an affair with the King, Francis I, probably angering his wife who she served as a lady in waiting.

In March of 1526, the papal enunciate Rodolfo Pio referred to her as “The Great Prostitute” which is a pretty scathing remark, although he wasn’t a very friendly source, and despised the Boleyn family.

Soon, Mary was recalled from France, and returned to her home country of England by 1520 to marry a gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber, named William Carey.

That same summer, Mary travelled with the King and his courtiers to the Field of the Cloth of Gold - a celebration of peace between rivals King Henry VIII and King Francis I. It was here that she would have seen her sister, Anne, again.

Their father, Thomas Boleyn, had helped plan the event as the Ambassador to France, and may have been in a good position to push his daughters forward for King Henry’s attention.

By 1522, it’s clear that Mary had caught the King’s eye. You see, Henry had an interesting habit of sending money to the husbands or fathers of the women he slept with.

That same year, Mary’s husband William received a few mysterious royal grants from Henry, which many interpret as evidence that Henry was compensating William for having an affair with his wife.

These royal grants lasted until 1525, which many assume to be the duration of their affair.

Although Henry and Mary were both married, this wasn’t an uncommon situation. It was expected for Kings to take mistresses, and for the mistresses husbands to keep quiet about it.

As you probably know, since we talk a lot about the Tudors on this channel, Henry had been married to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon since 1509, and their union had only resulted in one daughter, which was increasingly frustrating to Henry.

When compared with other kings, Henry was not quite as promiscuous. He only had 3 confirmed mistresses - Bessie Blount, Mary Boleyn, and later Madge Shelton, all of which began only when he was having marital difficulties.

However, there are many gifts and flirtations with other women recorded that may hint and other secret love affairs throughout the years.

In fact, we only know of the affairs with Bessie Blount and Mary because they were impossible for Henry to cover up. Bessie Blount bore him a son, whom he later legitimized, and Henry was forced to recognize Mary as his mistress because he had to ask for special permission from the pope to marry her sister Anne.

While we aren’t sure when Mary and Henry stopped being intimate, it’s been suggested that at least one if not both of her two children, born in 1524 and 1526, were fathered by the King. Unfortunately there is no evidence to confirm this either way, and the children were formally recognized as the children of her husband William.

Mary’s sister, Anne Boleyn

By 1526, Henry had moved on. But he hadn’t moved very far. His sights were now set on Mary’s sister, Anne. I’m dying to know Mary’s personal thoughts about this - whether she was jealous, or supportive of her sister. The two women had never been described as close, often moving in different circles.

There was probably some rivalry between them, and this may have been aggravated by the fact that Anne Boleyn reached the heights that her sister couldn’t. In 1533, Anne and Henry married - making Anne the Queen of England, and elevating the entire family to new heights.

One event in 1534 confirms a rift between the Boleyn sisters. Mary’s first husband had died of the mysterious sweating sickness in 1528. A few years later, Mary chose love over duty. She fell in love with a soldier from minor holdings named William Stafford. In 1534, they married secretly, knowing they never would have gotten permission for such a match now that her sister was the Queen. But soon, they were found out.

Anne was furious, and Mary was disowned from her family, and banished from the Tudor court.

While the financial circumstances for Mary and her new husband were dire, she wrote “I would rather beg my bread with him than to be the greatest Queen in Christendom.” which seems to be a direct insult to Anne.

Eventually, Anne gave in and sent her sister some money, but still wouldn’t allow her to come back to court.Sadly, the sisters would never see each other again - Anne Boleyn was executed on false charges of adultery in 1536.

We don’t have many records of Mary’s life after 1536. It’s probable that she lived in peace away from court with her husband, possibly having more children. She died of unknown causes in 1543.

As a sweet legacy, we know that both of her children, Catherine and Henry Carey, became close with Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth I and served her loyally as Queen.

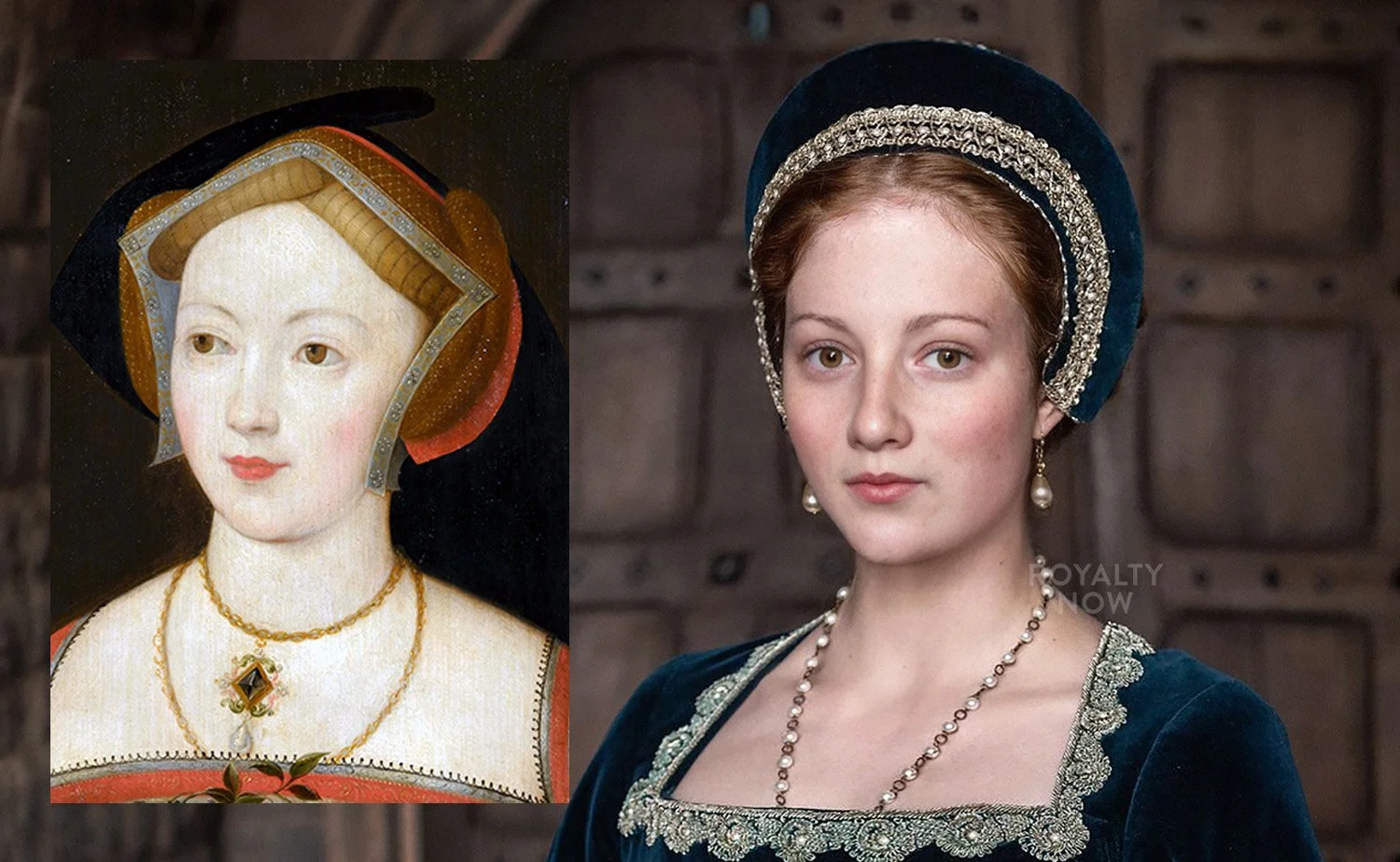

So let’s talk about what Mary really looked like and reveal the re-creations of her appearance.

Just a few years ago, an exciting discovery was made. This portrait of an anonymous Tudor woman had hung in Mary Queen of Scots bedchamber at Holyrood House for years. For a long time, it was believed that this woman’s identity was simply lost to history.

However, a new project (Jordaens Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project JVDPPP) confirmed that it was a lost portrait of Mary Boleyn.

Here’s how the team came to this conclusion. Originally, this portrait was one of a set of 14 “Beauties” - usually these were commissioned groups of portraits of royal women famous for their beauty. The set of paintings were dated to the 1630s, by Remigius van Leemput - well after Mary’s life. However, an inscription found in the National Portrait Gallery’s Archive matched the portrait to Mary.

Experts believe this portrait was a copy of an original Hans Holbein - the most prominent portrait artist in the Tudor court.

Aside from this image, there is very little known about Mary’s appearance. It’s always been rumored that she was the prettier, more voluptuous Boleyn sister - that she was the fair English Rose counterpart to her dark eyed, dark haired sister. But that’s what we have to go on - historical rumors, and this portrait.